Understanding MTTR

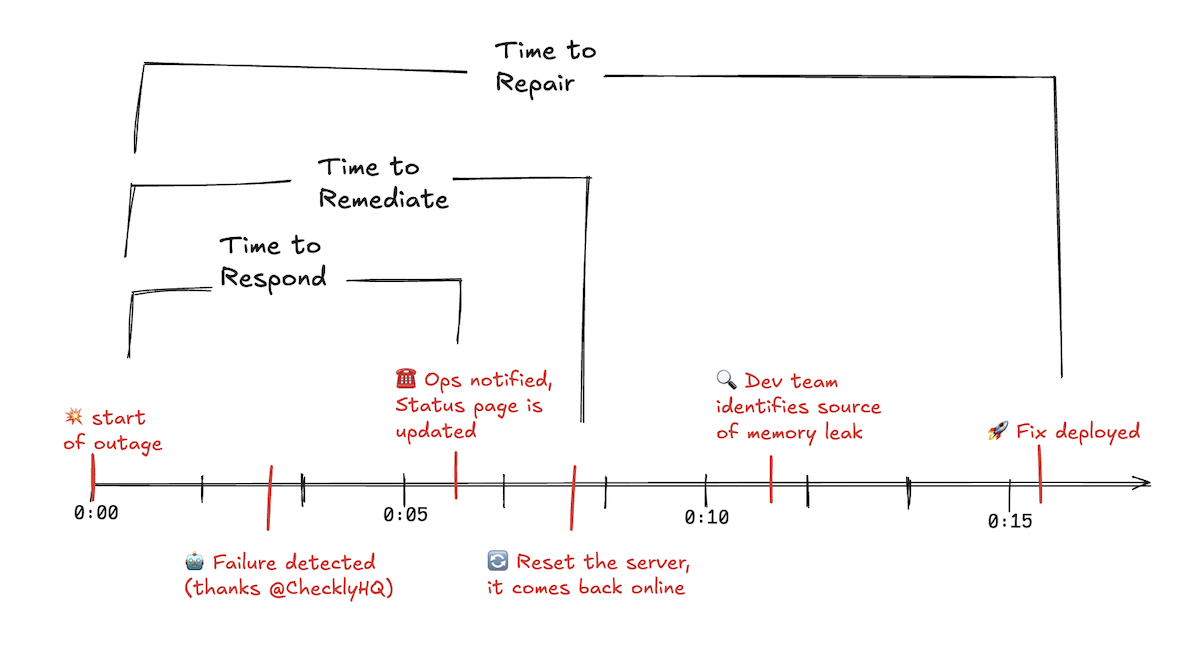

Originally a term from old school IT and even Operational services, MTTR used to refer to the time it took from a physical device’s breakdown to it its being back in service. For example, when an electric motor would break down, how long before a technician had analyzed the problem, fixed the motor, and it was back driving industrial machinery. MTTR stands for “mean time to repair,” but its definition can vary depending on whom you ask. Some interpret it as the time it takes to restore a system to a functional state, while others see it as the time required to completely fix the underlying issue. This ambiguity makes it difficult to benchmark MTTR across organizations, but it doesn’t explain why so many companies fail to meet their own internal targets. The confusion around MTTR is compounded by the fact that it is sometimes used interchangeably with other terms, such as:- Mean Time to Respond: The time it takes to acknowledge and begin addressing an issue.

- Mean Time to Restore: The time it takes to restore service after an outage.

- Mean Time to Remediate: The time it takes to fully resolve the root cause of a problem.

Calculating MTTR

The Mean Time to Repair is just the arithmetic mean (or average) of your time to resolution from all incidents. The timeline diagram above gives an example of how the time to repair is measured from each incident: it starts when the outage first occurred, to when a fix was deployed. If we had five incidents last month, with times to repair looking like the following table:| Incident Number | Time to Repair |

|---|---|

| 1 | 22 minutes |

| 2 | 9 minutes |

| 3 | 86 minutes |

| 4 | 21 minutes |

| 5 | 147 minutes |

How MTTR can fall short of measuring performance

It seems a simple thing to say ‘we want the minimum mean time to repair’ for a team and that the resulting optimization of the resolution process will result in better performance for users. As a very general critique, allow me to quote Goodhart’s Law:Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.When we first proposed MTTR as a measure for how well we were meeting our service level agreement (SLA) for our users, the connection between these statistics seemed irrefutable. But talking to senior Ops engineers you will hear many stories about how, despite improvements in MTTR and other metrics, users still complained of broken SLAs. One example: “We had an enterprise client complain we weren’t meeting our uptime agreement. This was after we’d streamlined the incident response process and put in hard controls for how downtime was measured. The issue it turned out was how slowly we marked downtime as ‘resolved’ on our status page. The client was monitoring that page and using it to show more downtime than we really had.” On the level of an individual conversation that can seem like a simple miscommunication, but take it from the user’s view: they rely on the status page to know when the service is available after an incident. If your team, despite fixing the issue quickly, is taking 20 minutes to remove the downtime status, isn’t that breaking your SLA?

Disagreements in measuring MTTR

The above example is a disagreement about what MTTR is measuring, with one person going by how long a service was unavailable based on backend logging, the other basing off the status page, but there are even more cases where it’s hard to agree on a value. What about geographically specific failures? If a service is unavailable in Germany only, does that geographic-specific outage count as downtime? What if one feature isn’t working for a week, but other users never notice the issue because they never use that feature? Both these questions ask ‘Does MTTR measure the whole system or just parts?’ and every organization will have its own answer to this question. To refer back to Goodhart’s Law mentioned in the above section, a confounding issue is the use of a general statistic to measure performance and (often) punish failure. When good engineers are facing penalties for missing SLA or hurting MTTR, they can often become very stingy with what counts as downtime.The right strategy for measuring MTTR

The best way to measure MTTR consistently is to use an automated synthetic monitor that’s agreed on before an incident. If a team is trying to examine an incident post-hoc and define the time points where downtime started and ended, motivated reasoning and multiple definitions will make the statistic less reliable. But if a monitoring service is checking often enough to measure both outages and recoveries in high resolution, this results in a statistic that all sides can agree on. Two additional features of a synthetic monitor should be considered, based on the disagreements about measurement that are so common:- Multiple geographic locations to ensure the service is up for all users

- Complex scripting and customization to ensure all core features are working with each check