How soon to communicate about incidents

There’s no single standard for communication time with users, ask different operations engineers, and you’ll get very different answers. To determine the correct time to contact users, consider asking the following general questions:- Do you want to notify users when you’re only investigating a problem, not even sure if it’s a technical failure on your service or a false report?

- Are you comfortable with users hearing about a failure that may not have an effect on them? For example, would you inform users of an outage even if it was limited to one geographic region, or would you want to limit who saw that communication to those in the affected region?

- In the last 5 incidents that generated feedback from users, how often was your team’s communication a major problem?

Automate communication when possible

During total outages, where some or all users are totally unable to use your service, no amount of delay in notifying affected users will feel acceptable to those users. Users expect that the second your service goes down, the login box on your page will be replaced with a ‘technical difficulties, please stand by’ message. While users always have high expectations, this one does feel reasonable: after all shouldn’t it be trivial to detect that a service is completely down, then list that on a status page automatically? On the other hand, we don’t want to tell users not to log in when the service is working fine. So while it’s best to automate status messages, we require a robust tool to detect these outages. You should, wherever possible, have an automated system that shows the availability of your service. Such an automated communication tool should do the following:- Regularly make requests of your key services

- Implement retry logic, checking again if any request fails

- Make requests from a broad geographic area, not relying on a single network route or availability zone

- Output the results of these checks to a publicly available status page

Trust your on-call team

As mentioned elsewhere in our guide to incident response playbooks, having a plan for dealing with outages and other issues is a huge source of psychological safety for an on-call team. However, while a plan is a good thing to have, you must always trust that your team will need to make their own decisions. I’ll draw an example from my own experience:One evening a sales person got in touch with the on-call team saying that the site was completely down. The sales person was at the client’s offices and had the site fail during a training as they were showing the interface to 100 engineers. Our tech support team member tried loading the same, frequently used, page and also got a 404 status. We spent a few minutes troubleshooting, switching to different accounts and making sure we weren’t dealing with an invalid browser cache. “Should we update the main page?” asked the tech support person. Clearly, if the site was completely unusable, we should make an update, but I asked her to wait. At the time I barely knew why I made that decision, but in retrospect I recall that I’d been waiting for the last few minutes for the page to load on a very slow mobile connection in our building’s basement. Sure enough, the page loaded fine. The office network was having a hardware problem. And the sales person on location? They’d been using a VPN to our network without realizing!In the case above, our team was tempted to notify tens of thousands of users of an outage that not one of them would have experienced. There is no hard and fast algorithmic path to deciding if all users need to be notified or a status page updated, there are always small and hard to define indications of an outage’s severity.

Delegate communications on the on-call team

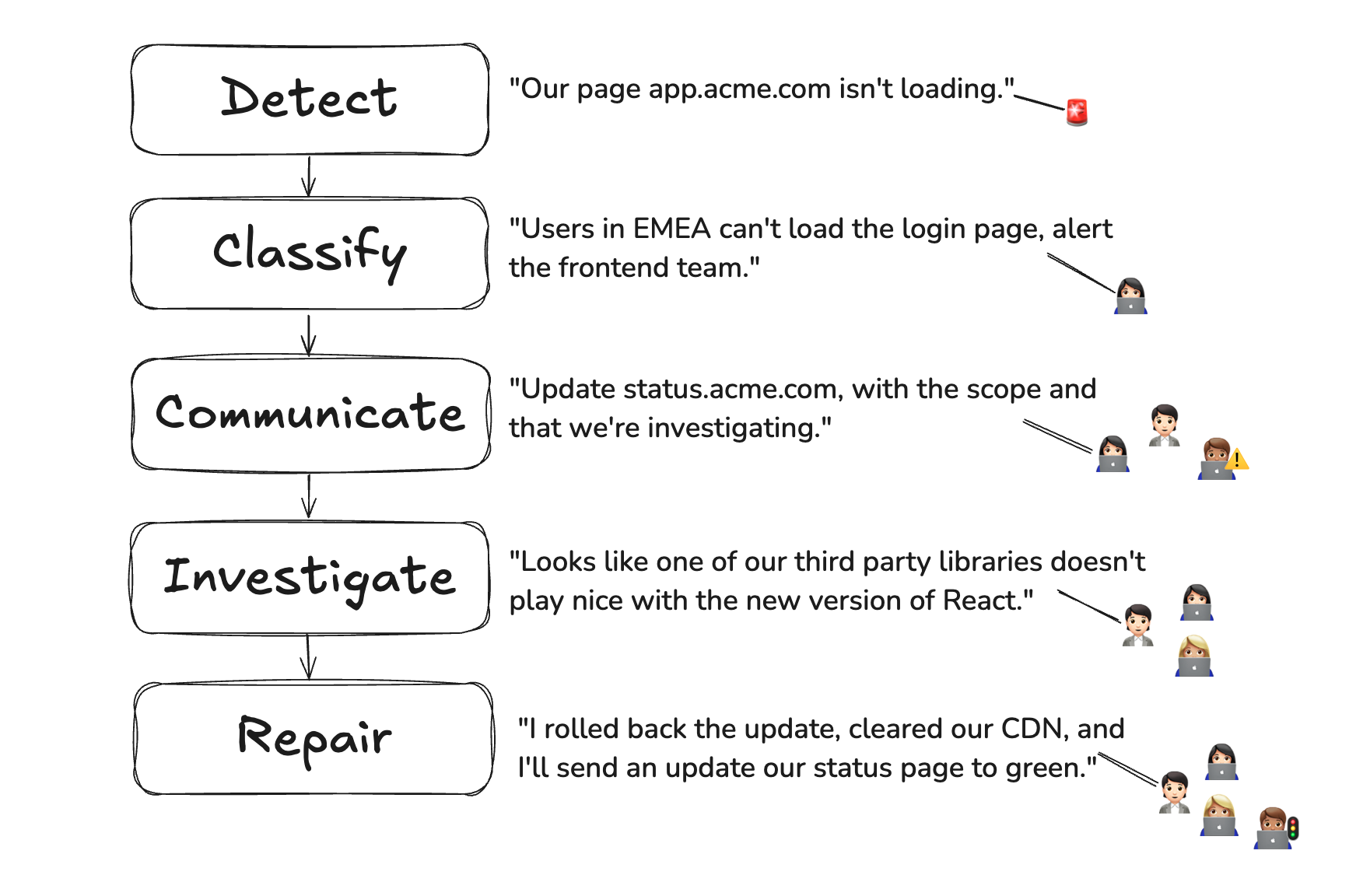

Any documentation of an incident response process will divide the response into separate stages of detection, classification, communication, et cetera.

- The support or sales engineer tasked with communication is likely to understand what exactly this outage means for most users, as users average behavior is more clear to someone who works with users directly.

- Customer-facing engineers are often the best people to identify expected behavior for the product, proving enormously helpful during the diagnosis stage.