How do we know our app is working?

We know our app is working by testing, but this begs the question: who should test what, when? Let’s take the tiniest possible failure: trailing whitespace in user data. Should the React frontend refuse to submit form fields with extra whitespace, should the application automatically remove whitespace before sending database requests, or should the DB controller automatically remove whitespace? The question: “in what layer should these checks happen?” brings us to the testing pyramid.The Testing Pyramid in Full

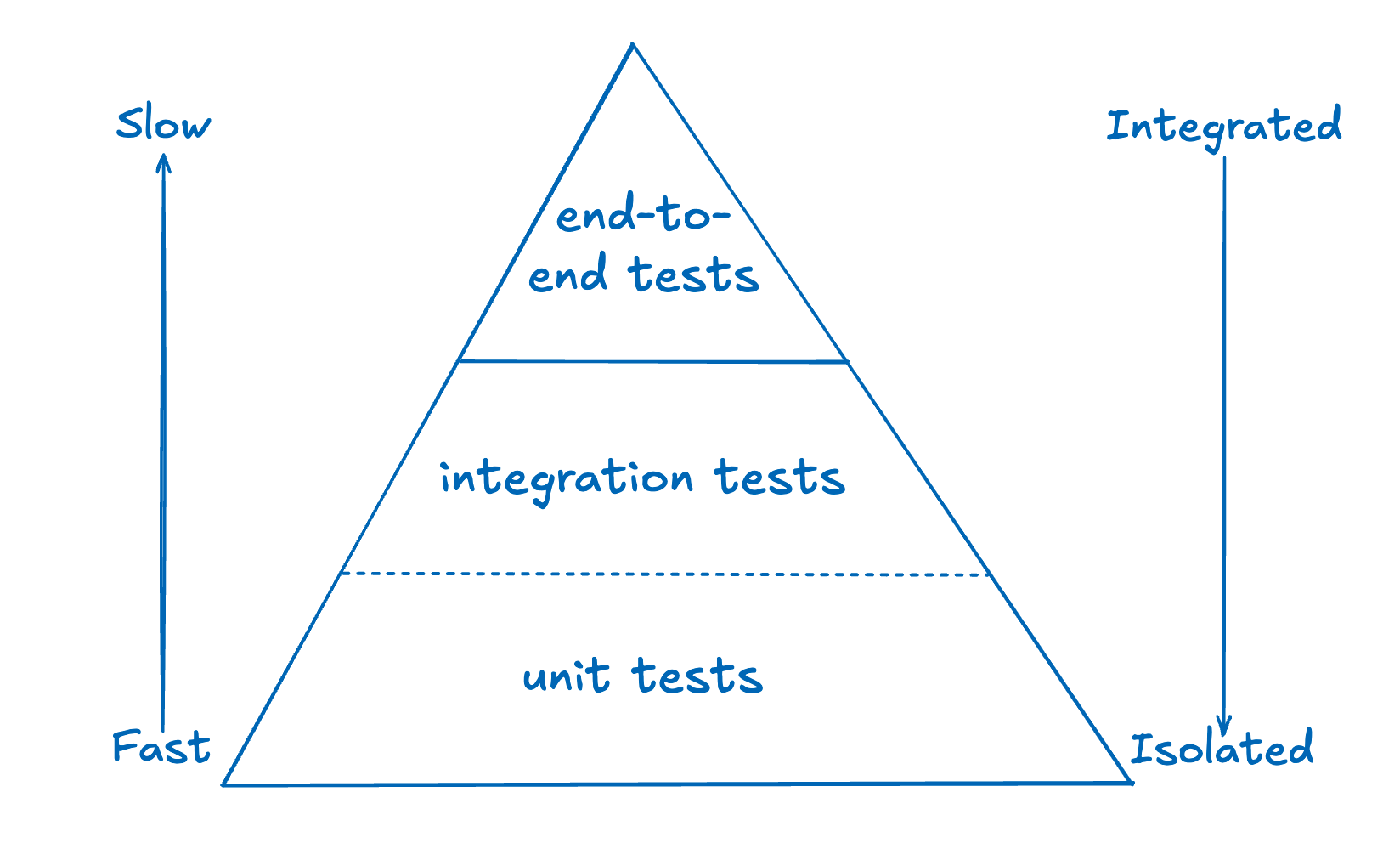

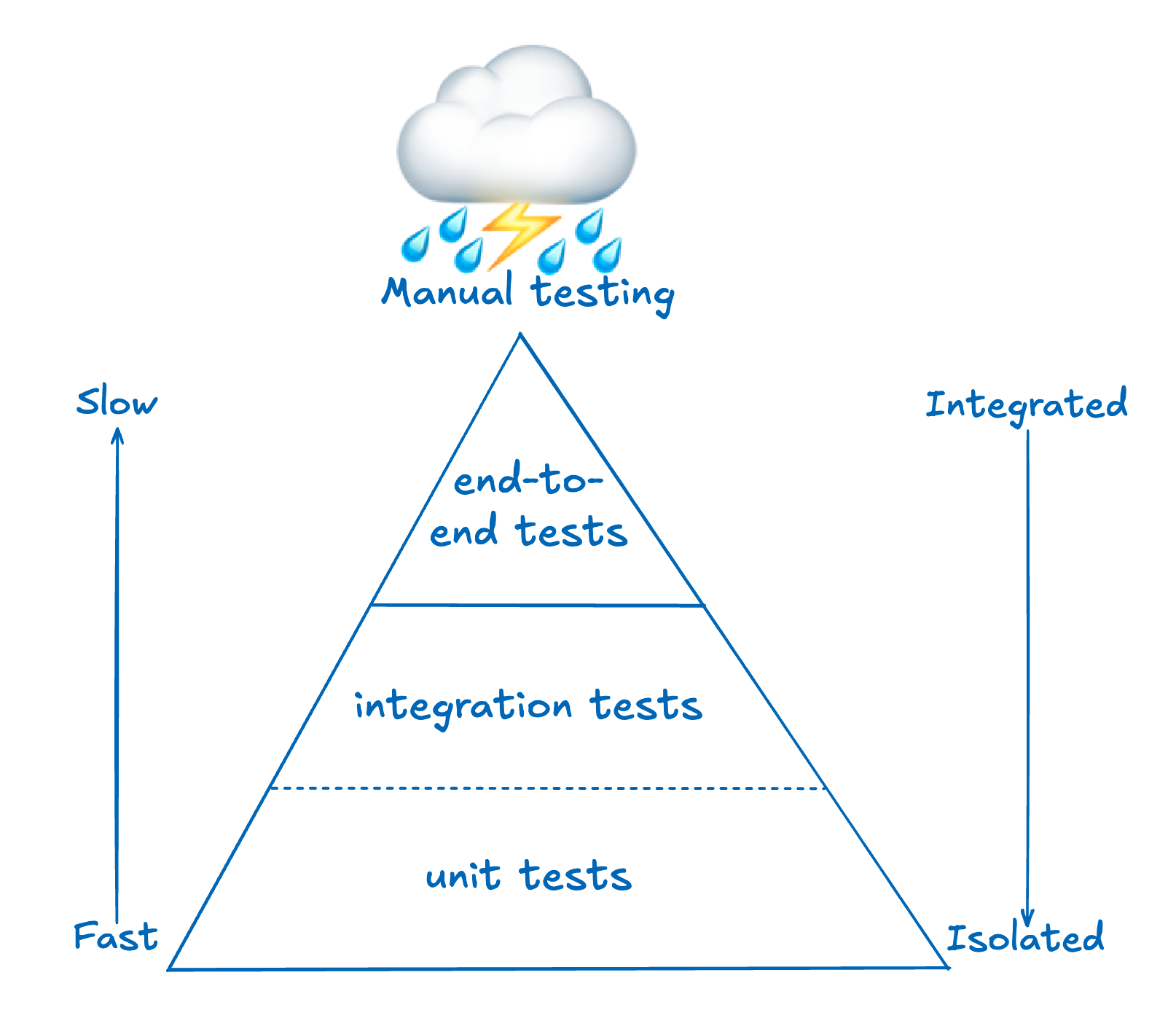

Originally conceived by Mike Cohn, and then popularized by Martin Fowler, the testing pyramid shows categories of tests, with the slowest on top and the fastest on the bottom.

- integration tests and unit tests are only separated by a dotted line since in practice they may not be technically distinct, and may even be written and run by the same team

- A second axis arrow indicates that on the bottom of the testing pyramid, the tests are more isolated, while on the top tests are naturally very integrated.

Unit Tests - with examples

A unit test is a highly isolated test that only works with a tiny chunk of code, possibly the code in a single file, or even a single function. A unit test is by its nature extremely high performance, and can run as frequently as the developer saves her work (or even with every entered newline). In the following example, we have the unit test for a single function callednoWhiteSpace

- They can (as this one does) work as effective documentation of what the tested code is supposed to do

- Unit tests could be written before the actual code, a process called Test-driven Development (TDD)

userPreferencesUpdate , and while our unit tests can test the code within that function, it can’t test the function working with real users. As such the unit test will feed in some fake user data and look at the function’s output, without reference to how real data stores, queues, routers, or other services might react. A unit test, then, exists in a universe of ‘stubs’ and ‘mocks’ which simulate the other services that make up your environment. To go one step further and either run or simulate larger chunks of your application, we go on to Integration tests.

Integration tests - something in the middle

Integrations test are supposed to show how well your code (or ideally your whole microservice) runs in something like your production environment. The layer includes two largely separate concepts:- Running your code in an environment where most of your application’s services are really running, and checking how it performs, looking for errors

- Creating stubs which give fake input to your microservice, and mocks which mechanistically simulate the other services, and testing that your service runs as designed

Integration testing’s more rigid cousin: contract testing

In microservice architecture, ideally microservices would interact in tightly controlled ways. The schema for communication, responses, and the logic of those responses can be clearly defined as rigid contracts between all services. Contract testing conceives a system where services can always be tested by sending fixed requests, and receiving responses that conform to those contracts. There are three primary concerns with an over-reliance on contract testing:- In trying to define completely fixed contracts on service interactions, you’re limiting the growth of your system as the complexity outstrips the ability of contract documentation.

- Contracts often expect consistent, readable information in data stores that doesn’t perfectly reflect reality.

- The nature of failures during service interaction is rarely due to ‘services not upholding their contracts’ and as such contract testing fails to find failures before users do.

End-to-end testing: testing like the users do

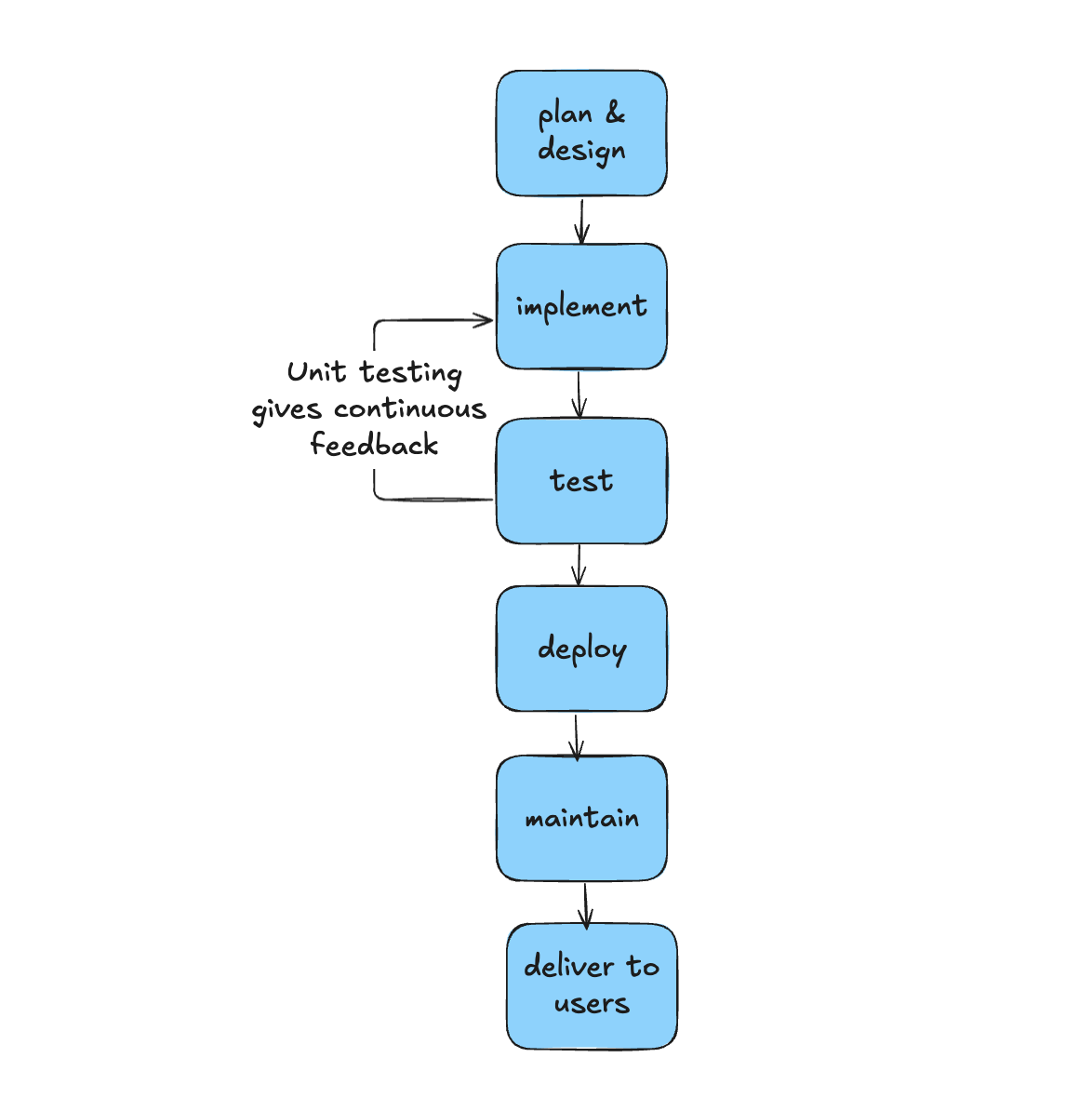

The testing period requires, an addition to reflect testing in the real world. After all, once all the pre-deployment testing is over, the production code rolled out, and the application is updated, don’t we all go check out the site to make sure it looks ‘right’?

From E2E Testing to E2E Monitoring

If we agree on the importance of end-to-end testing, it begs the question if testing should stop after deploy time. Thousands of unforseen interactions can break a production service even after the code is tested post-deployment, and our users are certainly using the service all the time. Shouldn’t our testing also continue after the code is out? For end-to-end testing on a cadence, there’s Checkly, which uses the power of playwright to test your sites, services, and APIs around the clock. Get started today!What problem is the testing pyramid trying to solve?

While it sadly causes many arguments about which tests belong where or which layer is most important, the testing pyramid is meant to acknowledge that each test type has a role to play, and the differences in performance is natural.Conclusions: Every Layer of Testing Matters

We care about testing because ultimately there’s one layer of testing that no one wants to use: our users. If there’s a bug, they’ll find it, if there’s holes in a data flow, their data will fall into it. If there’s an edge case our users will find it. And every time a user is the first one to detect a problem, it hurts their trust in our service.